Although MRI and EMG/NCV testing remained the gold standard for diagnosing disc herniation- and stenosis-related lumbar radiculopathy (aka: sciatica or radicular pain), carefully questioning of the patient with regard to the exact location of his or her radiating lower extremity pain is the next best thing to these expensive tests, for research has demonstrated that the presence of radicular pain that is isolated to one (or even two) dermatome (a patch of skin in the lower extremity that is supplied mainly by a solitary spinal nerve root) is more diagnostically accurate for radiculopathy then the classically taught examination findings of muscle weakness, sensory change, deep tendon reflex change, and straight leg raise test. [1-3]

Although MRI and EMG/NCV testing remained the gold standard for diagnosing disc herniation- and stenosis-related lumbar radiculopathy (aka: sciatica or radicular pain), carefully questioning of the patient with regard to the exact location of his or her radiating lower extremity pain is the next best thing to these expensive tests, for research has demonstrated that the presence of radicular pain that is isolated to one (or even two) dermatome (a patch of skin in the lower extremity that is supplied mainly by a solitary spinal nerve root) is more diagnostically accurate for radiculopathy then the classically taught examination findings of muscle weakness, sensory change, deep tendon reflex change, and straight leg raise test. [1-3]

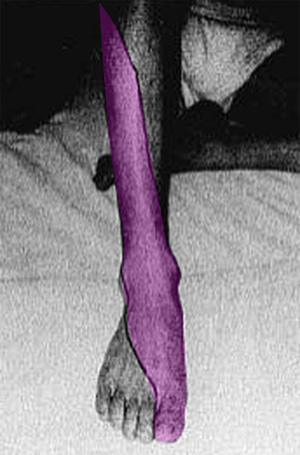

Figure left is an example of the right L5 dermatome (pink) in a patient suffering radicular pain from a large right paracentral disc herniation of the L4 disc. The right lateral thigh and buttock were also affected, but not shown.

Therefore, it is incredibly important that the clinician memorize the dermatomes of the lower and upper extremities because sooner or later a patient with radiculopathy will walk into your office and this serious condition needs to be caught early on, for successful discectomy is dependent on the timing of surgery. In other words, if a patient complains of radicular pain that is isolated to one or maybe two dermatomes, then MRI and EMG/NCV testing needs to be ordered right away.

Although the earliest mapping of dermatomes was performed way back in the 1800s, [6] the majority of dermatome charts which hang on the walls of many doctor offices today used data that were collected between 1913 [4] and 1968. [5]

The first well designed study on dermatomes was completed 1948 by Keegan et al. [7] who carefully recorded the skin pain-patterns of patients with surgically confirmed disc herniation. Unfortunately, this research was basically ignored by clinicians at the time.

In 1985, Kortelainen et al. [2] published the results of preoperative examination findings from 336 patients who underwent spine surgery for lumbar paracentral disc herniation at all levels of the spine (but mainly at L4 and L5). (*Please recall that a paracentral disc herniation is the most common and compress the traversing nerve root of the segment below. Therefore, an L4 paracentral disc herniation will compress the traversing L5 nerve root and usually affect the L5 dermatome.) The researchers reported that 93% of the group did in fact have radicular pain that was isolated to one (rarely two) dermatomes.

Using previously reported dermatome maps, they discovered that pain in the S1 dermatome was the result of the expected L5 disc herniation in only 63% of the cases. Thirty-four percent of the time, it was unexpectedly from an L4 herniation. Pain in the L5 dermatome was the result of the expected L4 disc herniation in 80% of the patients. In the remaining 20%, it was from an L5 disc herniation.

Disc herniations in the upper lumbar spine (L2 and L3) resulted in proper dermatomal radicular pain in only 10% of the patients! Ninty percent of the time, the radicular pain was experienced in both the L5 and S1 dermatome. *It should be noted that these results were based on a very small number of patients (N= 10), which is really statistically meaningless—upper level disc herniations are quite rare.

In 1993, Nitta et al. [8] published the results of a very well designed study which used fluoroscopically guided selective nerve root blocks to map the bottom three dermatomes (L4, L5, S1). Specifically, each patient had the nerve root (the one that was thought to be involved in his or her radicular pain) numbed with 1.5 mL of Xylocain, which was delivered via a transforaminal selective nerve root block . Once that nerve root was numbed, the corresponding distribution of skin numbness was drawn with a marker (mapped) on the entire lower extremity. (figure at top of page)

Here are the results of the study which still represent the best dermatome mapping ever completed, at least at the time of this writing (6/1/14). Also note the variability in these dermatomes. It is important to understand that not 100% of the patients will experience radicular pain in exactly the same portion of the lower extremity. In reality, dermatomes only give the clinician a rough idea of where in the spine spine the problem is at.

S1 RADICULAR PAIN:

If the L5 disc herniates into the lateral recess (which is where most disc herniations occur) and compresses / inflamed the traversing S1 nerve root, then the patient may suffer an S1 radicular pain (aka: S1 root-pain, or S1 sciatica).

If the L5 disc herniates into the lateral recess (which is where most disc herniations occur) and compresses / inflamed the traversing S1 nerve root, then the patient may suffer an S1 radicular pain (aka: S1 root-pain, or S1 sciatica).

Fig.#4 demonstrates the regions in the lower limb where the patient will most likely suffer the symptoms of S1 radicular pain. As you can see, the majority of patients (75%) suffer the burning, stinging, and numbing pain of sciatica in the lateral foot and outer half of the bottom of the foot, posterolateral leg, thigh, and buttock.

The S1 radicular pain is the result of axon damage and death of the small non-myelinated C-fibers that are contained within the traversing nerve root and arise in the S1 dermatome.

If the motor portion (portion of the nerve root which connects to muscle) of the S1 nerve root is damaged or irritated by the disc herniation, then the patient my suffer weakness and/or atrophy in the calf muscles (Gastrocnemiusmuscle), peroneal muscles (foot evertors), and/or the muscles that flex or curl the big toe.

The Achilles' Reflex and Plantar Reflex may also be diminished or absent with S1 radicular pain; however, almost half of the time deep tendon reflex testing will be completely inaccurate. [2].

L5 RADICULAR PAIN:

If the L4 disc herniates into the lateral recess, which is by far the most common type and level of disc herniation, [2] and compresses / inflames the L5 traversing nerve root, then the patient may suffer an L5 radicular pain (aka: L5 root-pain, or L5 sciatica).

If the L4 disc herniates into the lateral recess, which is by far the most common type and level of disc herniation, [2] and compresses / inflames the L5 traversing nerve root, then the patient may suffer an L5 radicular pain (aka: L5 root-pain, or L5 sciatica).

Fig. # 5 demonstrates the regions in the lower limb where the patient will most likely suffer the symptoms of L5 radicular pain. As you can see, the majority of patients (75%) suffer the burning, stinging, and numbing pain of sciatica on the top and inner portion (dorsum) of the foot, and the outer-front of the leg. In only 25% of the patients was the pain felt in the posterolateral thigh and buttock.

As mentioned above, the radicular pain is the result of axon irritability and death secondary to disc-herniation-related compression and inflammation.

If the motor portion (portion of the nerve root which connects to muscle) of the L5 nerve root is damaged by disc herniation, then the patient my suffer weakness in the Extensor Hallusis Longus muscle (muscle that lifts the big toe - * a classic finding) or the muscles that dorsi-flex the foot (lift the foot up).

If motor loss is severe, then the patient may experience a common symptom called foot drop that occurs while the patient is walking. Specifically, because of the weakness in the foot dorsiflexors, the patient will not be able to flex his foot far enough to clear the ground when walking and may trip or stumble over the foot. Other times the foot will slap to the ground while walking, again because the dorsiflexors of the foot are not strong enough to prevent the foot slap.

With regard to deep tendon reflex testing, there is no reflex associated with the L5 nerve root.

L4 RADICULAR PAIN:

If the L3 disc herniates into the lateral recess and compresses / inflames the descending L4 nerve root, the patient may suffer an L4 radicular pain (aka: L4 root-pain, or L4 sciatica).

If the L3 disc herniates into the lateral recess and compresses / inflames the descending L4 nerve root, the patient may suffer an L4 radicular pain (aka: L4 root-pain, or L4 sciatica).

Fig. # 6 demonstrates the regions in the lower limb where the patient will most likely suffer the symptoms of L4 sciatica. As you can see, the majority of patients (75%) suffer the burning, stinging, and numbing pain of sciatica in the anteromedial (front inner part) leg. Twenty-five percent of the patients will experience the pain in the anteromedial thigh, leg, and foot.

If the motor portion (portion of the nerve root which connects to muscle) of the L4 nerve root is damaged or irritated by the disc herniation, then the patient my suffer weakness in the quadriceps muscle (muscle that extend the knee). If severe, the patient may not be unable to perform a squat or get out of a chair because.

If the problem is severe, the patient a have a diminished or absent Patellar Reflex (aka: knee jerk). However, the patellar reflex was found to be incredibly unreliable as an indication of radiculopathy and really should not be used. [2]

You should not use dermatomes to predict the exact level of disc herniation or lateral stenosis, for they are just not super accurate. [2,8,9] On the other hand, patient-complaints of dermatomal pain are surprisingly accurate at predicting the presence of the symptomatic disc herniation or lateral stenosis that has resulted in true radiculopathy. [1,2]

Therefore, all healthcare providers should provide every new patient with a document (traditionally called a Pain Diagram) that allows him or her to specifically draw the regions of pain within their lower extremities.

I know from my own encounters with numerous pain management doctors, orthopedists, neurologists, and spine surgeons, that very very few of them provide this important document and thereby immediately reduce the accuracy of their evaluation.

In this day and age of post-Obama care, the patient has to be incredibly proactive in their healthcare management. Therefore, it is a good idea for you to complete the pain diagram on your own and present it to the doctor during our evaluation. Hopefully, the doctor will be current enough on his or her research to understand the importance of it. (Download the Pain Diagram)

1) Hancock MJ, Koes B, Ostelo R, Peul W. Diagnostic accuracy of the clinical examination in identifying the level of herniation in patients with sciatica. Spine 2011; 36:E712-E719.

2) Kortelainen P, Puranen J, Koivisto E, et al. Symptoms and signs of sciatica and their relation to the localization of the lumbar disc herniation. Spine 1985; 10:88-92.

3) Al Nezari NH, et al. Neurological examination of the peripheral nervous system to diagnose lumbar spinal disc herniation with suspected radiculopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J 2013;13:657-674.

4) Foerster O: "Zur kenntniss der spinalen segmentinnervation der muskelin." Neurol Zbl 32:1202-1214, 1913

5) Uihlein A, et al. "neurologic changes, surgical treatment, and post operation evaluation. Symposium: Low back and sciatic pain." J Bone Joint Surg 50A:1, 1968

6) Bolk L. "Die Segmentaldifferenzigrung des menschlichen Rumpfes und seiner Extremitaten." morphol Jahrb 1898 - 1899; 25:465-543; 26:91-211; 27:630-711;28:105-46

7) Konstantinou K, Dunn KM. "Sciatica: review of epidemiological studies and prevalence estimates." Spine 2008;33:2464-2472.

8) Nitta H, et al. "Study on dermatomes by means of selective lumbar spinal nerve root block." Spine 1993;18:1782-1786.

9) Taylor CS, Coxon AJ, Watson PC, et al. Do L5 and S1 nerve root compressions produce radicular pain and a dermatomal pattern? Spine 2013;38:995-998.