ANNULAR TEARS:

The Cause | Physiology | Types of Annular Tears| Healing | radial tear | concentric tears | rim lesion |

Pertinent Anatomy Review for Annular Tears:

As we have learned from the "Anatomy Page," the disc is made up of two parts: a Jell-O-like center called the nucleus pulposus (nucleus) and a tire-tread-like periphery called the annulus fibrosis (annulus) (see figure #1).

Normally, the nucleus is held (or corralled) firmly in place by the tougher annulus fibrosus. Under this ideal situation, the biomechanics of the motion segment (a motion segment is a disc, which is sandwiched inbetween two vertebrae) are such that the nucleus will bear the majority (~80%) of the tremendous downward weight of the body (the axial load), which spares the pain-sensitive posterior annulus from the majority of this stress.

The facet joints also carry about 20% of the axial load.

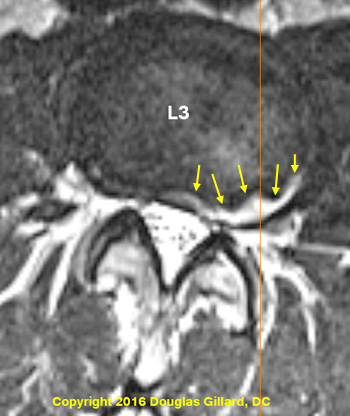

The picture to the left demonstrates a massive concentric annular tear which is superimposed upon a broad-based disc herniation. This client had severe low back pain with pain radiating from the low back, on to the top of the left thigh. It is located from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock and is bright white (radial opaque or hyperintense) in color, secondary to a wicked inflammation process.. Can't see it? Then click here.

How Does It Occur?

As we age, the ability of the annulus to contain the pressurized nucleus will become compromised secondary to a drying and weakening phenomenon (called degenerative disc disease) that occurs in all discs (especially in the 40s). As a result, the nucleus may rip its way through the annulus and cause an annular tear. The annular tear not only changes the axial load biomechanics of the disc (now the weight shifts posteriorly onto the pain-carrying nociceptive fiber of the sinuvertebral nerves and overloadsthe facet joints), but also releases evil biochemicals called cytokines [especially tumor necrosis factor alpha] into the now-exposed sinuvertebral nerves endings. Bottom line, severe low back pain can result in some patients (but, confusingly, not all patients). This type pain is called "discogenic pain."

AKA: note to the grammar police: in Europe, annulus is spelled anulus.

Pathophysiology and the Sequelae off Annular Tears:

The annulus of the disc is made of crisscrossing sheets of collagen called lamellae (like a tire tread kind of), which are normally tremendously strong and pliable. In fact biomechanical compression studies have demonstrated that the vertebrae themselves will fracture under experimentally induced loads before the annulus succumbs. With normal age, however,the annulus tends to lose strength and pliability which makes it more susceptible to the development of annular tears.

In some patients, this degenerative process can be greatly accelerated by lifestyles that involve heavy labor or are extraordinarily sedentary. Genetics is also known to play a significant factor in pathological disc degeneration. For example, some patients may have genes that give rise to inferior types of disc-building-materials ( i.e., proteoglycans and/or different types of collagen and even elastic tissue).

Although there are different "flavors" of annular tears, radial annular tears are the most common and begin within the inner annulus (adjacent to the nucleus) and then work their way toward the pain-sensitive periphery of the annulus, which (as noted above in the figure one legend) is filled with pain-carrying nerve fiber called the sinuvertebral nerves.

The Latest research (2012) dictates that the actual discogenic pain that a patient feels may result from a combination of two things: (1) evil biochemicals called cytokines, which are spawned from the degenerated disc itself (especially the nucleus pulposus) which, because of the passageway created by the annular tear, come in contact with the nociceptive (pain producing) nerve endings in the outer annulus and initiate a painful inflammatory process; and (2) biomechanical changes which have resulted secondary to the new passageway communicating the nucleus with the outer annulus (i.e., the annular tear) which causes a loss of hydraulic pressure within the nucleus and redistributes loadbearing from the center of the nucleus on to the posterior annulus (which is exactly where we don't want the axial load to be, because this is where all the pain fiber is). Now, mechanical compression of the already inflamed sinuvertebral nerves may cause severe discogenic pain. In other words, the pain is because the sinuvertebral nerves within the posterior annulus have become "activated" with inflammation (which may cause pain in and of itself) and compressed by the weight of the body because the biomechanics of the disc have been changed by the annular tear from the center of the disc to the posterior periphery.

The other thing that is important to understand is that some patients can have annular tears without having any associated pain. It is still not completely understood why some patients suffer horrible pain with annular tears and others don't. It probably has something to do with individual sensitivity to the cytokines and/or the patient's own immune response to the chemical exposure upon the sinuvertebral nerves.

The other thing that is important to understand is that some patients can have annular tears without having any associated pain. It is still not completely understood why some patients suffer horrible pain with annular tears and others don't. It probably has something to do with individual sensitivity to the cytokines and/or the patient's own immune response to the chemical exposure upon the sinuvertebral nerves.

The picture left (T2 axial) demonstrates a massive concentric annular tear (yellow arrows) within the posterolateral L5 disc.

Sidebar: hopefully you've been to my MRI page and studied how to view MRI images. If not, please go to my MRI page, or check out my YouTube videos on "How to Read Your MRI." Once you get the hang of it, you will be able to really appreciate what this pathology looks like.

Concentric annular tears, as we will soon learn, occur between the lamellae of the disc, and not through the lamellae (at least not yet). Why did I say, "at least not yet"? Because it is known that concentric annular tears typically turn into full thickness radial annular tears with the passage of time.

This patient had severe anterior thigh pain, with associated low back pain. I know some of you are asking, "how can they have leg pain"? It's usually secondary to a referral of pain from the sinuvertebral nerves of the torn disc.

Although many times you don't see an annular tear on MRI, sometimes, when there is a lot of inflammation going on, they can become visible, even without gadolinium enhancement. Such was the case of the patient depicted an image left– this was not a gadolinium-enhanced MRI!

The Types of Annular Tear:

Radial Tears | Rim Lesions | Concentric Tears |

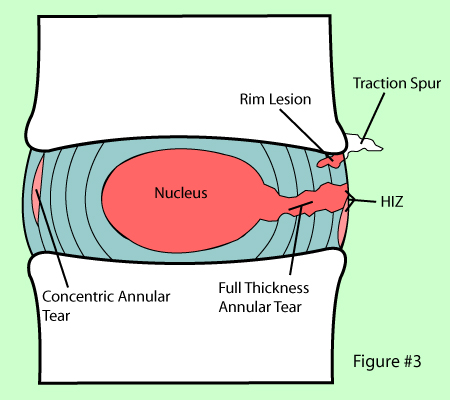

As noted in figure #3, there are three main types of annular tears (aka: annular fissures) that occur in the human disc:

The rim lesion, is a horizontal tearing of the very outer annular fibers of the disc near their attachments into the ring apophysis (i.e. the Sharpey's Fibers). It's sort of like a reverse radial tear, because it starts from the outside in works itself toward the nucleus.

The concentric tear is a splitting apart of the lamellae of the annulus in a circumferential direction. This one tends to occur in either the posterior or posterolateral region of the disc which unfortunately is where all the nociceptors (pain sensors) live.

The radial tear, (aka: full thickness annular tear) is a horizontally orientated annular tear that that begins in the nucleus pulposus and then tears its way toward the periphery of the disc (see figure #2).

Such a tear may allow the pressurized nucleus pulposus to squirt through the tear, out the back of the disc and into the epidural space, which in turn may compress the adjacent nerve roots--such a condition is called a disc herniation, which you can read all about on my disc herniation page.

I have created a webpage for each one of these tears which can be further explored by simply clicking here.

Annular Tear Healing

Like most other injuries, the body will attempt to heal the annular tear by filling in the gap with scar tissue. depending on the amount of degeneration within the disc, anecdotally, healing times can be 18 months or even more. New blood vessels will grow from the periphery of the disc down toward the nucleus through the annular tear (it is these blood vessels in part that supplied the building blocks needed for the scar tissue to form). Unfortunately, pain-carrying new nerve fiber acompany the blood vessels down into the center of the disc! This is not a good thing, because now has a higher capacity to generate pain because it has more pain-carrying nerve fiber within it. This phenomenon, as well as a similar phenomenon which may occur vertebral endplate, is most likely the reason why patients with annular tears often suffer bouts of pain throughout their lives..

How to Diagnose a Symptomatic Annular Tear?

The only way to know for sure whether or not a disc has suffered an annular tear is by a test called discography. Although you can read much more about it on my discography page, it involves the injection of a radiopaque dye into this nucleus pulposus (center) of the disc. The contrast is forced into the disc which causes the pressure within the disc to rise. The goal of the procedure is to re-create the patient's usual and customary pain (i.e., concordant pain). If such pain was re-created, then the disc is said to be concordantly positive (i.e. that disc is generating "discogenic pain")and assumed to be the pain generator.

In order to further validate this finding, lidocaine (a powerful anesthetic) may be injected into the disc to see if the pain will now disappear--the theory being that the lidocaine numbs the inflamed sinuvertebral nerves, which in turn takes away the pain. Then, the disc above or below (assuming it is not a suspect for annular tear) is tested in the same manner in hopes of finding that disc to be non-painful (i.e., a control disc). While all this is happening, the patient is blinded to what is going on (i.e., the doctor does not tell the patient which disc he's injecting and what to expect).

Ideally, a CT scan should be performed after discography is completed in order to qualify the "flavor" of annular tear and whether or not that tear was leaking contrast material into the epidural space.

The History of Annular Tear

Annular tears were first described by Schmorl and Hunghanns in 1932, but were more officially categorized by Hirsh and Schajowicz in 1952 and 1971(2) into the available flavors that we have today. Specifically, they described Concentric Tears as crescentic or oval cavities which were filled with fluid or mucoid material between lamellae of the annulus. These defects were a result of disruption of the short transverse fibers of the lamellae (these fibers hold the lamellae together), probably due to torsional forces (twisting) on the disc from repetitive twisting/turning movements or rotational type injury.

They also described Radial Tears as fissures extending from the surface of the annulus to the nucleus, as well as Transverse annular tears(aka: rim lesions) as tears in the very outer fibers of the annulus (Sharpey’s Fibers) near their insertion point at the ring apophysis (very outer portion of the bony vertebral endplate).

Since these initial descriptions, we have learned a lot more about annular tears, secondary to extensively studied both microscopically and macroscopically. Famed researcher Barrie Vernon-Roberts, who has devoted over 25 years of his career to the study of annular tears and disc degeneration, has published several papers on the subject in 1977, 1990, 1992, and final in 1997. To date, his 1992 paper entitled “Annular Tears & Disc Degeneration in the Lumbar Spine” contains one of the best descriptions of the three types of annular disc lesions yet written. I will use his research frequently through out this page. (3)

In a Volvo Award Winning paper, Roberts also laid to rest the erroneous theory that all three types of annular tears were interrelated(4), by demonstrating that a radial annular tear begins as a "cleft" from the nucleus and moves into the inner annulus. It next steadily progress outward until it finally makes its way into the outer periphery of the annulus fibrosus, which of course is infested with pain carrying nerve fiber. (5,6).

Now, let's talk a little more about each specific type of annular tear:

THE FAMILY OF ANNULAR TEARS

Radial Tears | Rim Lesions | Concentric Tears

References for this page:

1) Hirsch C, Schajowicz F, Acta Orthop Scand 1952;22:184-223

2) Schmorl G, Junghans H, “The human spine in health & disease”. New York: Grune & Stratton, 1971

3) Osti OL, Vernon-Roberts B, et al. “Annular Tears & Disc Degeneration” J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1992; 74-B:678-82

4) Kirkaldy-Willis WH, “The pathology & pathogenesis of low back pain. Managing Low back pain” New York, Churchill-Livingstone, 1983; pp 23-43

5) Osti OL, et al “Volvo Award- Anulus Tears & Intervertebral Disc Degeneration" – Spine 1990; 15(8):762-766

6) Vernon-Robert B, et al. “Pathogenesis of Tears of the Anulus”, - Spine 1997; 22(22):2641-46

30) Coppes NH, et al. “Innervation of anulus fibrosus in Low Back Pain.” Lancet 1990; 336:189-190

31) Freemont AJ, et al. “nerve in-growth into the diseased IVD in chronic back pain.” – Lancet 1997; 350:178-181

32) Ross JS, Modic MT, Masaryk TJ, AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990 Jan;154(1):159-62